Fuga: The Music Theory behind Energy Pillars

Mastering the flow of energy is the Zen aspect of music-making, and involves an understanding of positive and negative energy. This energy is made up of several different energy fields that overlap. Getting beneath the surface of energy movement, which can be reduced to quite simple pathways guided by Energy Pillars, requires delving into each individual energy field and seeing how the notes are affected by them. Each field must be separated and explored with as much depth as possible. Although this seems impossible at first, it’s quite plausible and practicable.

In order to master the flow of energy, you need not only understand the movement of energy on a local level, but also the larger architecture – how thetectonic plates of form revolve around one another, creating a multi-layered monarchic form.

Beyond the inner movement of pure energy, as it’s fleshed out and clothed in color and emotion, a psychological depth not unlike a human being, or even a group of human beings, reveals itself. A psychologist amateur musician friend of mine, during a discussion about emotional counterpoint – how each voice has its own inner life separate from all the others but at the same time inter-connected by a common bind of time, space and fate – exclaimed excitedly, It’s just like family therapy! Each individual inhabits his own reality but the family unit has its own dynamic that influences and is influenced by the individuals that make it up.

Music theory and analysis are not simply about understanding the harmony and basic musical form. This is simply scratching the surface, and in an abstract sense does little for the performer.

My approach to analysis of harmony and energy is not dissimilar to the Italian notion of appoggio, centering one’s energy and support in the points of greater emotional tension and expression. Relative dissonance is generally the essence of harmonic expression and each harmonic pattern creates its own energy field with positive and negative pulls. Rhythms and meters also each have their own energy fields, and as they play off each other, juxtaposed against the ebb and flow of the many levels of harmonic and melodic movement, a complex web of energy emerges, which when properly understood however, can be simplified with Mozartian precision. The important points of each musical gesture can be easily identified like pressure points and brought out, aligning the energy fields, clarifying the surrounding architecture, and heightening the meaning and effect.

The prerequisite for the following argument is a basic understanding of Music Theory. Whether you possess this or not, remember that understanding how to choose the Energy Pillars is less important than believing in their existence and taking your best guess. More often than not, your intuition will give you the correct answer. And even when it does not, choosing a Pillar and organizing your energy around it will focus your interpretation and give it clearer meaning while giving you all the other physical and emotional benefits of balanced, non-static energy. Skim over this and come back later if it’s too difficult.

This subject in and of itself is the subject for life-time study and deserves a book of its own – Music Theory for Performers (perhaps someone will get around to writing it one day…). I took many Theory courses as an Undergrad and Graduate student, required and elective, and all left me unfulfilled by their simplistic and dry nature. No course frustrates the Performance Major more – most perceive it as the antithesis of performing and either try NOT to learn it for fear of being corrupted by academia, or learn it enough simply to pass the course, and then quickly forget it because they never use it. Few theory teachers are performers themselves; many of them are composers who are forced to teach it and suffer through it as much as their pupils. Others are Theorists who love the beauty of abstract, useless ideas. And even they find no pleasure in teaching the rudiments of their craft to unenthusiastic, half-asleep students.

If only theory could be viewed as a tool to perform better. If only the two could be seen as two sides to the same coin! Then performers would flock to it and lap it up! If they could be actively linked and constantly applied to the performer’s craft, students would develop quite a different attitude toward theory. Theory as a discipline would be reborn in a sense. What could at first be an elective Theory Course for Music majors with a pre-requisite of First-Year Theory could later become a unified approach to Theory and be taught from the beginning as Theory 101. After all, music needn’t be separated from its performance; all musicians are performers.

This is what my approach is about. Start from the performer’s perception of energy, color, emotion, and form. What truth does he instinctively possess? How does Theory apply to his actual experiences playing music? How can he learn to analyze his own energy and the energy hidden in a page of music and somehow unite them logically? Shouldn’t this be the goal of Theory?

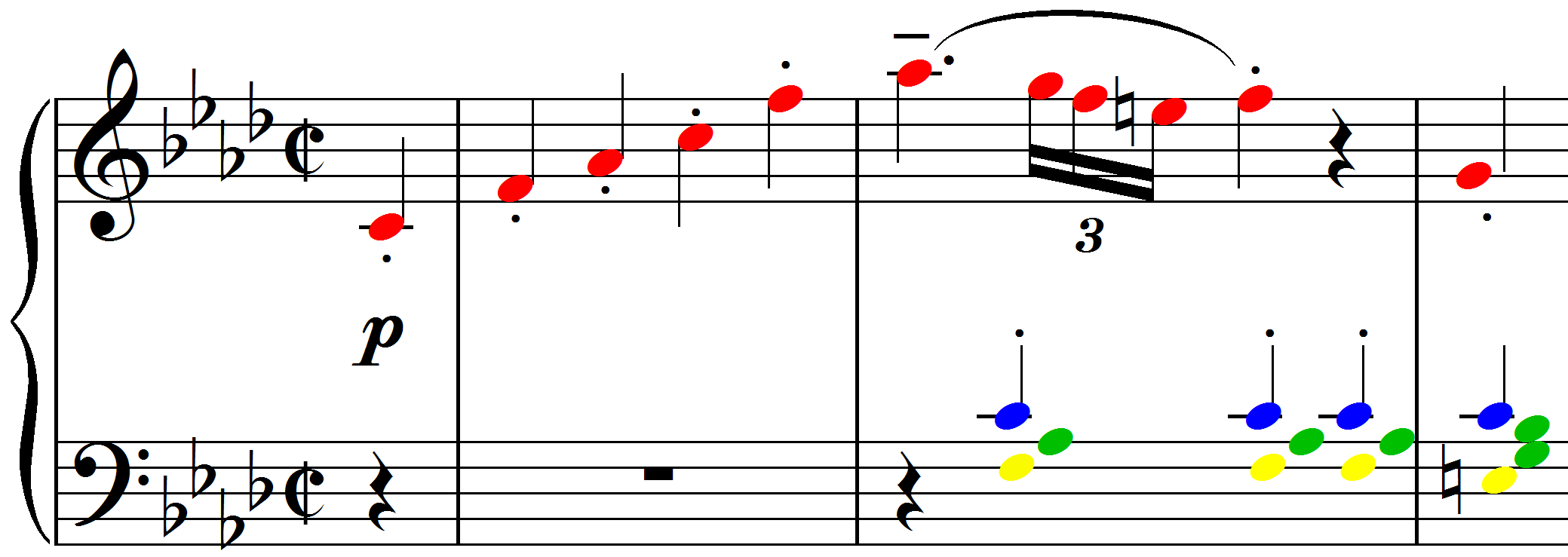

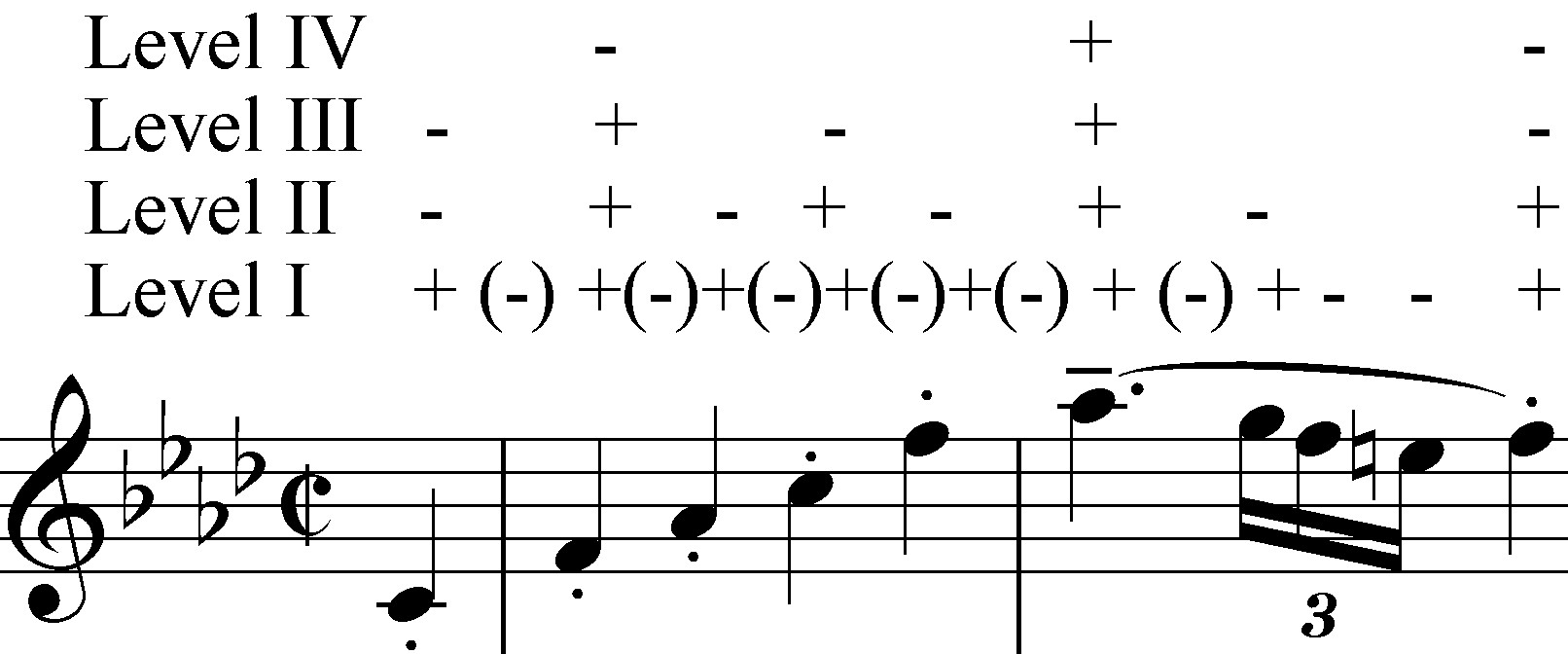

Let’s start with a basic example from the 2nd movement of Beethoven’s final Piano Sonata, Op. 111.

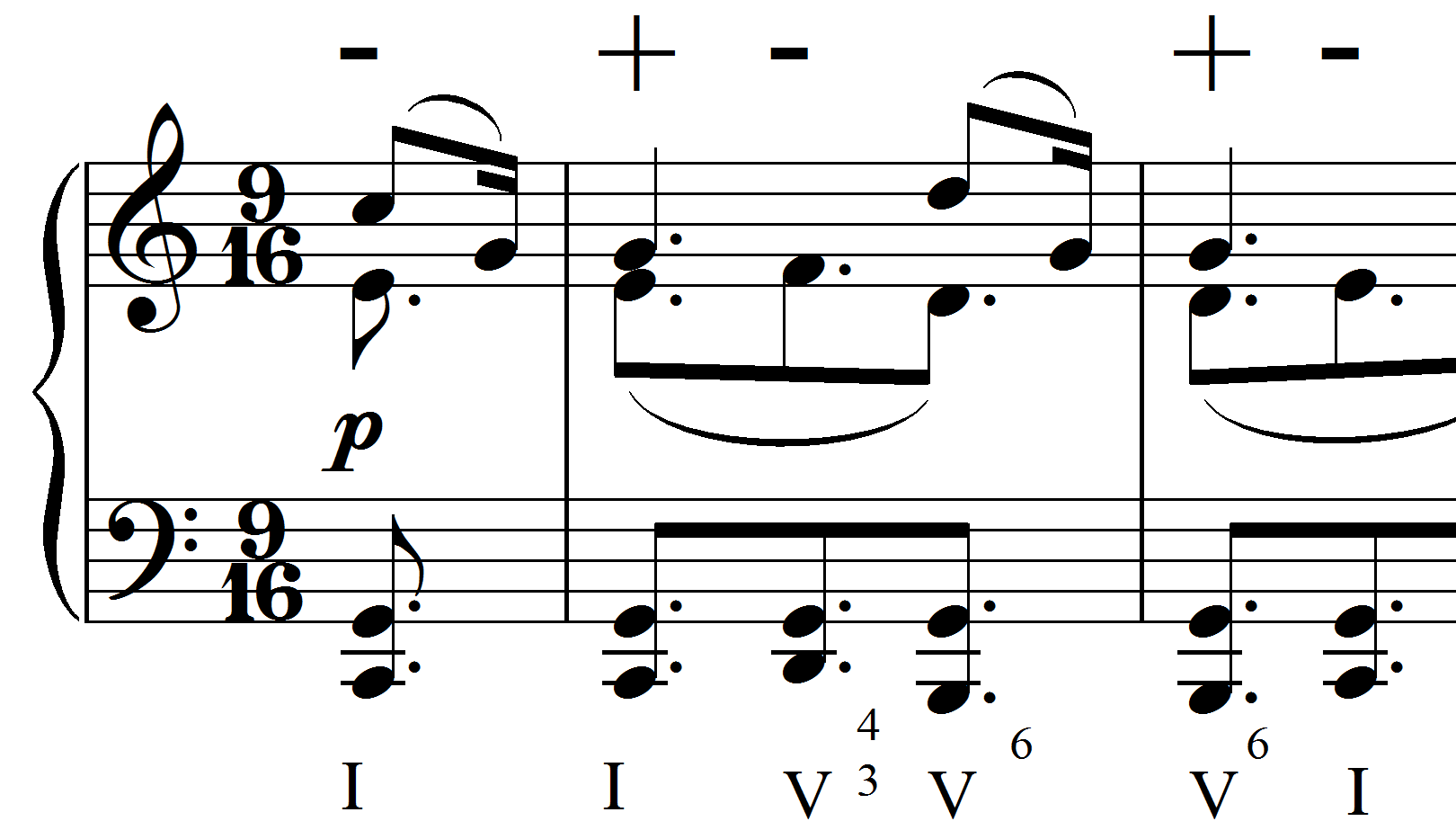

If we analyze the harmony of the first couple measures with Roman numerals, it looks like this:

It’s in C major and the chords are all primary. Granted that a IV-chord or a V-chord generally possesses more energy/tension than a I-chord, you would assume that those chords in the first two bars might be accented, like so:

However, the performance major will tell you, No! That’s not so . . . what’s the point of analyzing harmony if it doesn’t tell you anything about the music?

If you take the normal performer’s view of the energy in these bars, it will look like so:

But how can you justify it theoretically?

The four basic types of energy that define Energy Pillars, listed in order of importance, are as follows: 1) Harmonic Dissonance (both appoggiaturas within a chord, and relative dissonances between chords); 2) Meter, 3) Note-value (the relative length of the notes), and 4) Note-height (how high or low the pitches are relative to one another).

Harmonic Dissonance

In Western Music, Harmonic Dissonance is the single most important factor in determining relative energy value between notes and between chords. Meter is a close second because it’s difficult to determine whether dissonance is passing or accented without knowing where it’s placed rhythmically. However, even before there was meter, such as in Gregorian Chant, music balanced itself between positive and negative poles. Look at the movement of energy in the following Chant in Dorian Mode { in modern notation }:

Ascending stepwise from the tonic D, we land at our first Pillar on the 6th degree of the scale, which is more dissonant than its 5 lower neighbors and is accented expressively. The following F and A then act as passing notes into an accented G, the dissonant 4th degree of the scale, which then descends stepwise through F, E and D until the C, our second main Pillar. This dissonant 7th degree of the scale is accented as a brief appoggiatura, resolving through the E and C and finally settling back into the consonant, Tonic D.

I can’t allow myself here to drawn into a several-hundred-page-long dissertation about the relative value of harmonies, but suffice it to say for the present that every chord in a composition has a relative energy value to all the other chords in the work. No two chords, even when appearing identical, can possibly share the same energy value because they are influenced by their placement in time. It’s important at first to gain a conscious command of feeling the relative dissonance between any two chords side-by-side. Analyze them in terms of traditional notation and the perceived movement of energy, and try to decide which one has more dissonance. Usually, the answer presents itself readily once asked. Seek and you shall find – provided you know the right questions.

Move through a phrase step by step until you’ve established the relative harmonic dissonances, then step back and compare the more harmonically charged chords to one another to see which one is more dissonant. As you move away from the work and see its larger harmonic movement, you’ll see how it’s generally motored by relative dissonance between harmonies.

Melodic dissonance is a close second in determining the movement of harmonic energy. An incredible amount of energy can be released by simply introducing melodic dissonance into an otherwise relatively consonant chord. A poignant moment of dissonant consonance is expressed in the final appoggiatura from the Aria of Bach’s Goldberg Variations (played on the beat as a long eighth-note):

These harmonic principles will be explored as we move through examples in this essay, and again in several examples throughout Part IV.

Meter

Meter is another enormous subject beyond the confines of this book, but certain basic ideas need to be understood. Meter alone produces its own energy spheres. Each meter has a basic energy pattern that cycles bar after bar. Each individual beat makes up a meter in itself, and inside the beat, the possibility for infinite inner meters is theoretically possible.

Let’s look at a few basic meters.

In 2/4, beat one is strong and beat two weak; beat one is positive and beat two negative.

3/4 is a little more complex. Beat one is the strong beat, beat two the weakest, and beat 3 slightly stronger. Beat one is positive and beats two and three are negative, however beat 3 is positive in relationship to beat two.

4/4 is even more complex. Beat one, as always, is the strongest. Beat three is the second strongest, beat four the third and beat two the weakest, such that beat three is negative to beat one, but positive to beats two and four, which always remain negative. Beat four is usually stronger than beat two, as it’s drawn into the energy of the downbeat.

Compound meters combine two simple meters. 6/8, for example, is basically 2/4, each beat divided by three. The parameters change slightly though because beat six can’t be so weak that it’s not able to lead into beat one. Therefore, beat six is only slightly weaker than beat 4.

Any individual beat can be defined as a meter or combination of meters – we’ll look at examples of that later on.

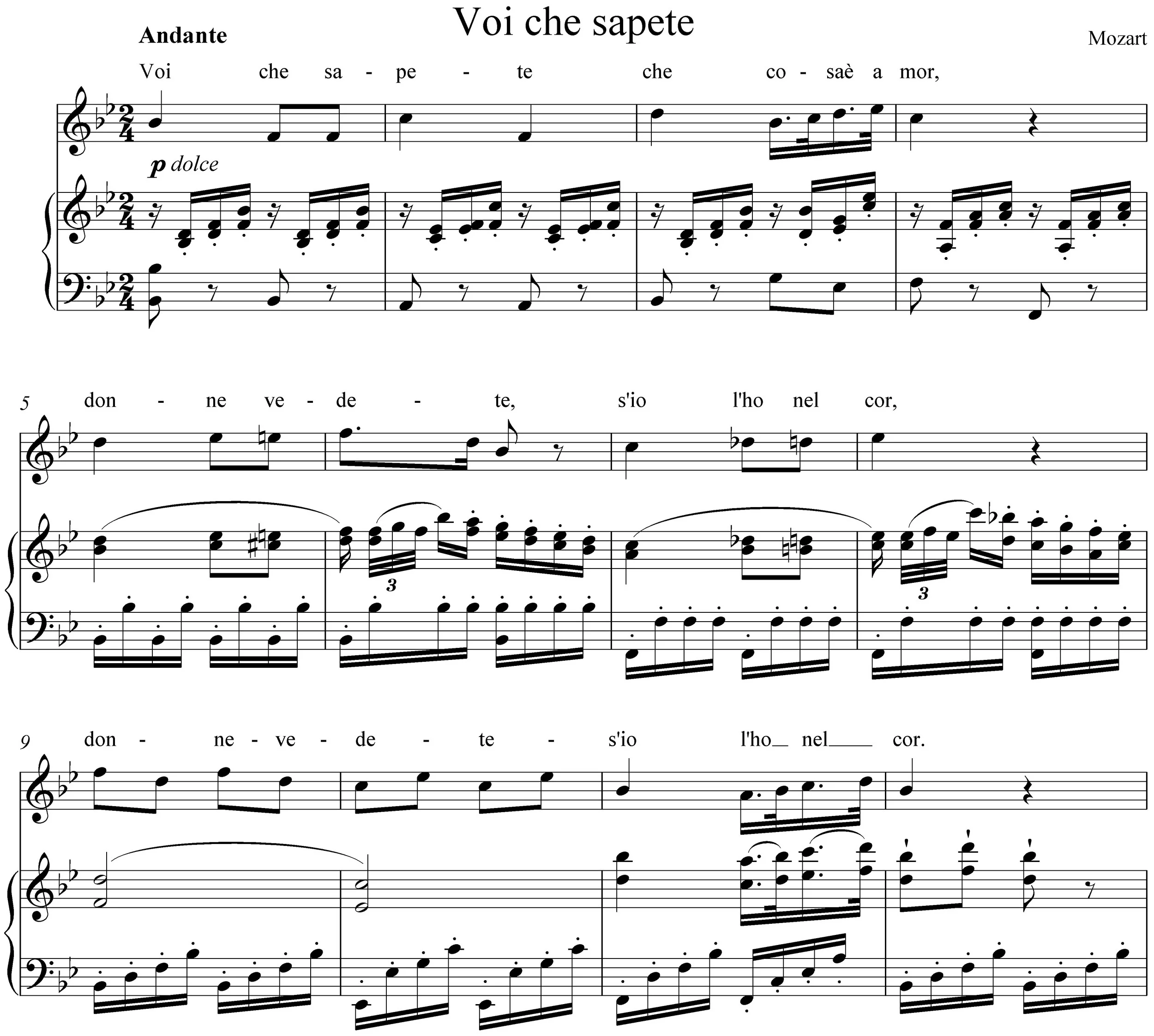

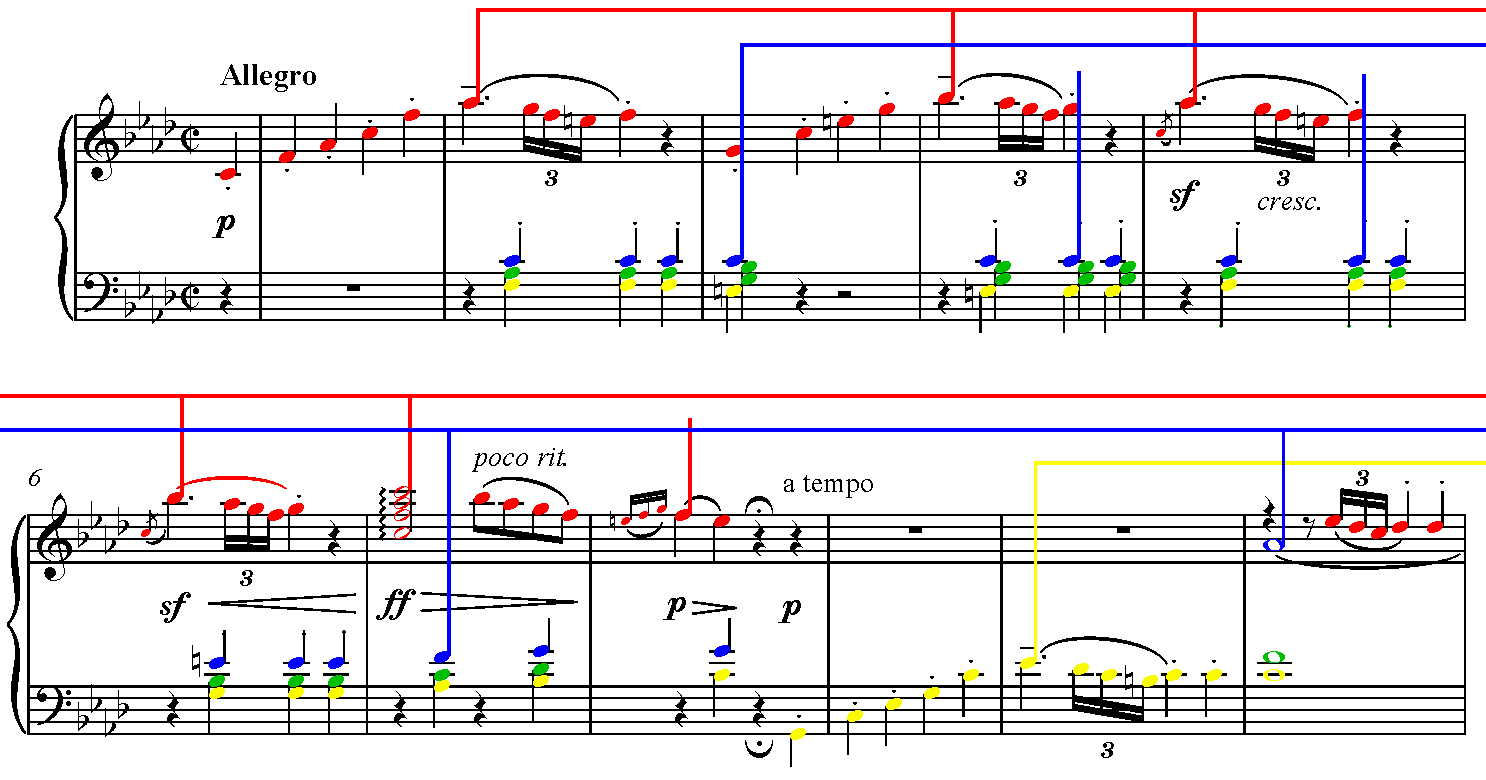

The mystery of meter is that its power is constantly in flux depending on the strength and dominance of other energy fields. It is often negated to the point of being unrecognizable on the surface. Only occasionally is it experienced in its purest, absolute rhythmic form, often in accompanimental figures. Yet it constantly exists below the surface. Let’s look for a moment at Mozart’s Aria, Voi che sapete, from Nozze di Figaro.

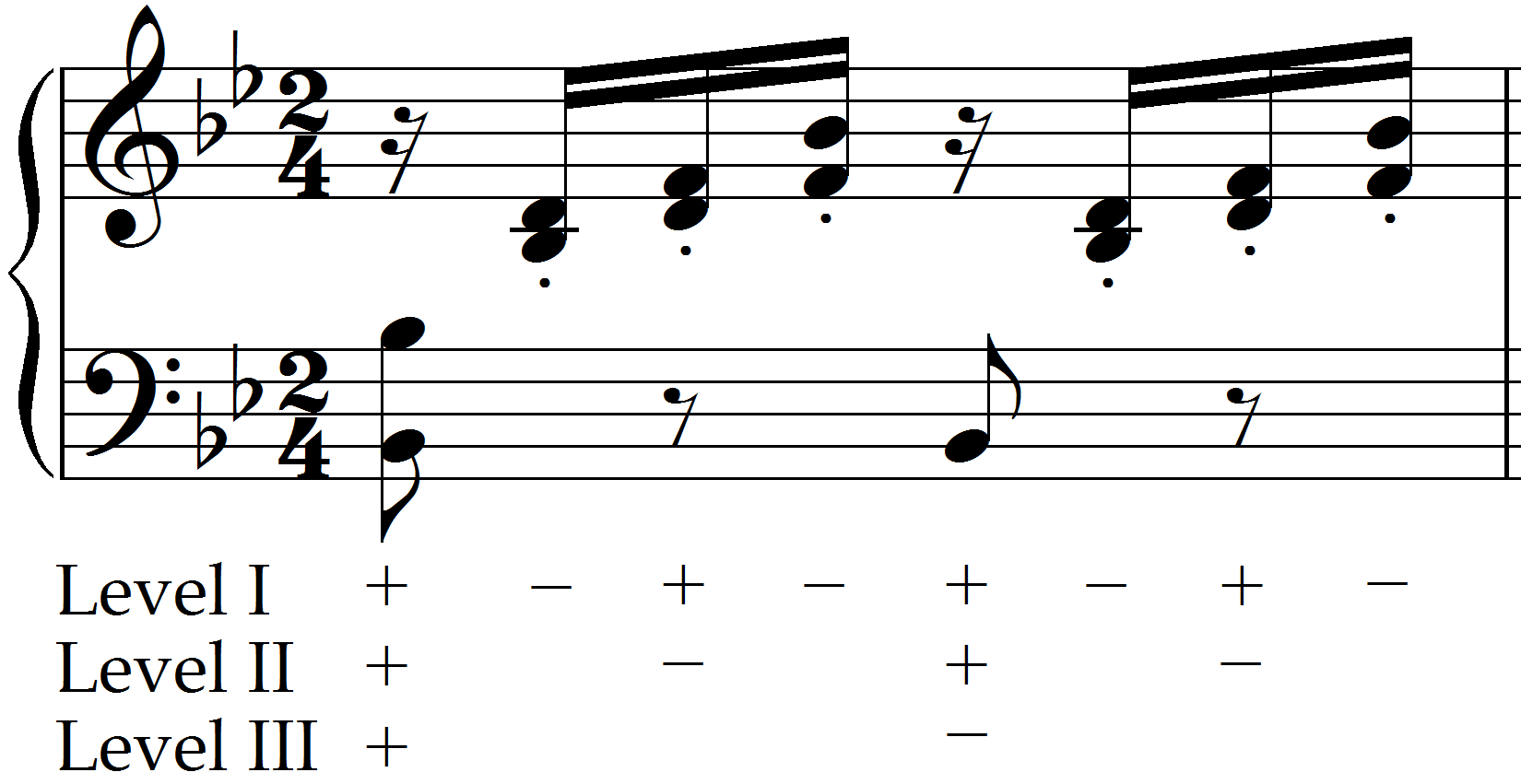

Both the melody and the accompaniment bubble with rhythmic and metric vitality. Let’s look first at the accompaniment. The constant, regular sixteenth notes (string pizzicato in orchestration) arpeggiating slow-moving primary harmonies, cleanly respect the metric energy fields - positive always balanced by negative.

{In the above example, Level I represents the metric field at the sixteenth-note level, Level II at the eighth-note level, and Level III at the quarter note level.}

This is true also of the melody:

{Here Level I represents the Metric Field at the eighth-note level and Level II at the quarter-note level.}

Interestingly though, if we look at the complete first phrase of the vocal line (the first four bars), the energy and expression of the Italian text sometimes overrides the underlying metric and harmonic energy. Voi che sapete che cosa è amor {You who knows what love is, or word-for-word, you (Voi) che (that) sapete (knows) che (what) cosa (thing) è (is) amor (love).} In Italian, this phrase can be interpreted and accented in several different ways, depending on the desired inflection. Mozart’s setting of the words seems to imply that he deems the che on the downbeat of m. 3 as the primary accent. After all, he places it on the highest tone, on a downbeat, and exactly in the middle of the phrase, which lends it symmetric beauty. If you recite the Italian this way though, it sounds awkward. It would be more natural to emphasize VOI or CO(sa) or (a)MOR, or all three, in relative values, than CHE. So the sensitive singer needs to find a way of respecting Mozart’s musical setting while also observing the rhythmic and metric values of the original text.

This is the world of the Singer and the Vocal Accompanist, if you venture into the vocal repertoire, you must take into account this other dimension of energy, character and style, often even during the instrumental interludes. Sometimes I wonder if purely instrumental works as well are not sometimes influenced by the energy and even diction of the silent, unformed words that accompany them. Endless volumes have been written about programmatic undercurrents of “pure” music, but what of the hidden languages behind the programs? Although we won’t be able to enter such discussions here, we will briefly return to a discussion of the rhythm and energy of speech in a later essay.

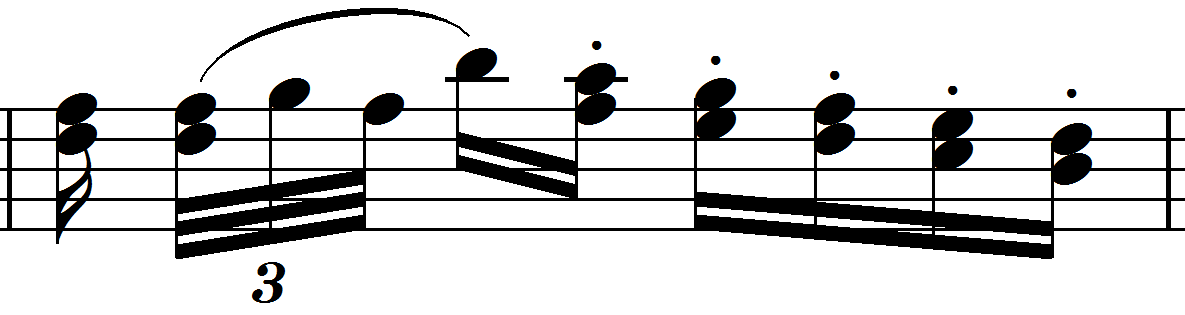

Now let’s look for a moment at a couple examples of inner meter in the above example. Here is the treble accompaniment of bar 6:

The triplet on the second sixteenth of the first beat reveals an inner 3/32 meter. That is, in the time of a single sixteenth note, the metric laws of triple meter are observed. Any beat or fraction of a beat can subdivide into Micro-meters, each revolving around, or inside of, the larger meter. At the other end, bars often group into Macro-meters, such that four bars of 2/4, say, can form a single 4/2, or two bars of 2/2. The above four-bar phrase of Voi che sapete can be interpreted either way.

As you analyze musical examples from not only Modern Music, but from all periods of music, you’ll discover every manner of Micro- and Macro-meters, as well as other complex and cross meters, often extending over the boundaries of tradition metric definitions and even phrase definitions.

As you become more aware of the interacting energy fields of meters, of how larger complex meters are formed by grouping bars into macro-meters, your playing will gain in depth, dimension and meaning.

A useful exercise with any work or passage is to play it to through first observing the Micro-meters as closely and exaggeratedly as possible. Then take a step back to the next Micro-meter level or to the notated Meter level. Then take another step back playing each bar as 2/2 – cut time. Then as 1/1, with an eye to linking bars into Macro-meters. (In case I’ve lost any of you with hypothetical time signatures, 1/1 would mean that there is one beat per bar and that a whole note equals one beat.) When dealing with grouped bars, treat the metric laws more freely; the main accent, like many dances, may be on an unusual beat.

If you were to apply this exercise to the first four bars of Voi che sapete, you could begin by realizing it as if it were in 4/8, say, then as written, in 2/4, then 1/2 (one beat to the bar, a half-note equals one beat), and then grouping two bars together into a larger macro-measure, 2/2, then four together, 4/2.

Another useful exercise to develop a greater sensitivity to meter and to its forward-propelled movement is to superimpose rhythms upon a phrase of music as you play it, as if a tambourine we’re silently accompanying you with rhythmic verve.

Above a bar of music in 2/4 with sixteenth notes, you could superimpose the following rhythm, for example:

or

If triplets are at play, you could superimpose this rhythm:

or

All of these rhythmic juxtapositions propel you into the downbeat and accent the dance-like roots of meter. They give the downbeat accent, but also lift; they downplay the weak 2nd beat by hiding it in the shadow of the downbeat; and they propel the anacrusis (upbeat) into the downbeat.

Returning to our argument, another idea to consider briefly is that the accompaniment, especially an accompaniment of such dance-like character as this, attaches itself to and indeed defines itself by the underlying metric values. Melodies, in general, are less beholden to meter because they define themselves either by their ignorance of it or their freedom from it. Melodies ride the meter but are usually not obviously defined by it. It’s just as wrong to kill the meter by expressively belaboring the melody as it is to trifle-ize the melody by making it too metric.

Sometimes Meter’s power is not real but virtual. The expectations of Meter are ingrained in the listener’s psyche to such an extent that variations from it on the surface are interpreted as expressive deviations from a hidden metric field. Deviations from meter constitute metric dissonance, which is the essence of metric espressivo, a principal element of rubato.

{The concept of the listener’s perceptions changing the actual substance of the music and becoming an active element of the interpretation is a fascinating subject of its own outside the scope of this book.}

Note-value

Go into the long note. This is one of those pieces of advice that you can virtually trust blindly because 95% of the time, it works perfectly and the other 5% at least passably.

There’s a reason why certain notes are longer; generally it’s because they’re more important. And I’m not simply referring to whole-notes and half-notes; gestures very often find their peak in a relatively long note - be it a whole-note, dotted-quarter-note, eighth-note or dotted-thirty-second-note.

Rhythm operates outside of Meter and produces its own energy field, whether we’re talking about a miniscule gesture or the arch of an entire Opera or recital. Rhythm and Meter are of course linked and constantly play off one another, but it’s important to be able to separate them and perceive their unique energies in order to be able to flow with them and to be able to manipulate them for expressive purposes.

The Shorter the note, the lighter it should be played. And vice-versa. Not observing this truth regularly will make your playing pedantic; observing it indiscriminately will make it lack expression. A wonderful old-school Italian conductor once pointed out to me, In Puccini, it’s the short notes that are expressive, not the long ones!

The reason this is often true in Puccini and in Romantic music in general, is because by fighting against natural rhythmic and metric laws, the melody asserts itself expressively.

Rhythmic Characterization falls into this general discussion on Rhythm and again is a subject far too complex and vast for the confines of this book. Besides, Rhythm is generally best experienced rather than read about. I was once lent a wonderfully complex book about Rhythm – more than 600 pages long in small print. The weight of it in my back-pack made me feel a little more important. I made it through the first several pages zealously, then opened a page of music and started searching on my own from primary sources.

Every rhythm has a special character with relative weight-distribution. As you begin categorizing rhythmic patterns for yourself, take note of each pattern’s common characteristics and how they change depending on the tempo and the meters they’re placed against. The same dotted rhythm, for example, can be flippant or deathly serious depending on context.

Note-height

All music is essential either vocal or vocally derived. Because of the nature of vocal technique, as the pitch rises, the energy level also rises. The highest pitches in one’s vocal range require an inordinate amount of energy to emit and sustain. The Soprano or Tenor’s high-C, for instance, is so intense and its communicative power so expressive that when sung well, it brings the house down. An untrained singer will tend to sing with a natural crescendo/diminuendo as the melody moves up and down. This is simply the natural order of things.

However, notes are often governed by other energy sources that negate the desire of higher notes to be louder than their lower neighbors. One of the great difficulties of mastering singing is to overcome this technical hurdle, to make it seem quite often that the higher note requires less physical/mental/emotional energy than lower ones.

Pianists are often so disconnected from their voice that moving up doesn’t make them sense a growing vocal intensity. Singers on the other hand are trained so extensively to use an increase in energy every time their voice rises that they have a hard time seeing music and phrasing in any other light.

Analysis for Performance

Once you come to terms with how the above types of musical energy can be reduced to energy spheres broken down into positive and negative points, you’ll notice where several fields line up to suggest the overarching flow of energy. Often though, the data contradicts itself, and one form of energy must impose itself at the expense of the others. How this happens is often mysterious. The definition of the arc of energy, the Super-melody, is your most important goal as an interpreter because it corresponds most completely with your energy experience during performance.

But, like analyzing the stock market or any other complex system, divining it requires experience and intuition. Obviously, inserting all the data into a super-computer wouldn’t result in the ultimate musical solution, or even an artistic one. And more often than not, the performer will stumble upon a valid solution without being able to define it theoretically, and thereby refine it. Conversely, theorists sometimes spin beautifully logical theories that have little to do with the actual performance of a work; contemplating such theories at length, or worse, trying to express them through performance, may result in a less-than- inspired evening. There’s nothing so painful as a Piano recital serving as a pedagogical demonstration.

As you come to better understand your options and the energies inspiring your mind and emotions, your choices will become more self-evident; while at first your mind may become cluttered with too much data, once you’ve sorted out what’s essential, your mind will become clearer, your vision long, and your emotional expression purer and more direct.

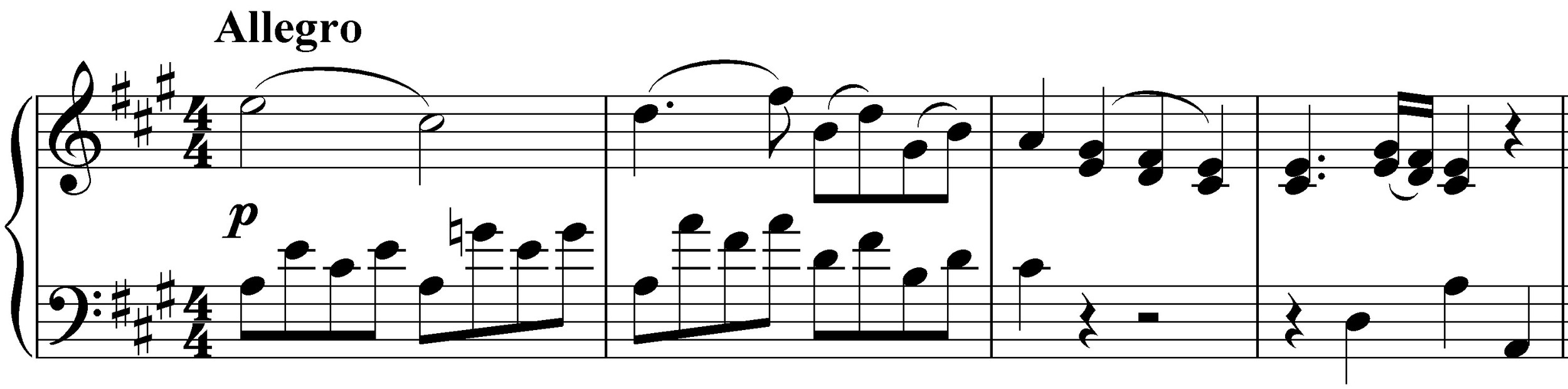

Now, let’s return to analyzing the opening bars of the Beethoven example above and see why the energy moves the way it does. Here is the manuscript in Beethoven’s own hand, which lays out the architecture of the long phrase in stark relief while shrouding the smaller inner gestures in mystery.

Certain details are striking! Notice how he writes each of the hairpin crescendo-diminuendos as a single arch – the energy is solid and intense, with no space to escape or breathe as it swells and peaks. Never have I seen any edition of Beethoven that demonstrates this peculiarly Beethovenian notation. Notice also the size of the first crescendo leading into m. 6; it’s the largest single marking so far in the score! There’s no ambiguity that we’ve arrived at the climax of the first phrase.

Consider also the spacing of the notes – is it possible to divine how Beethoven imagined the pacing of the phrase, its rubato? Notice how each of the beats in the first two measures are spaced quite regularly and relatively close together, as if simply defining a pulse, molto semplice. Then suddenly the downbeat of m. 3 is delayed considerably; the vision of the long phrase to come harkens breadth and reflection, as if taking in infinity’s aurora. The second beat of the same measure is delayed even further as the melody soars up a 6th to an “E” – cantabile! The first two beats of m. 4 again take on the regular, compact spacing of the first two measures, but the third beat is delayed – why? Perhaps he needs to set off the sudden, dramatic ascent into the climax through the following measure. Indeed, m. 5 again is spaced more broadly, especially the third beat, palpably delaying the arrival to the climax on the following downbeat.

Could all this be mere coincidence? It seems as if he’s breathing and singing across time through his quill. Shouldn’t an urtext edition strive to recapture the revealing idiosyncrasies of the manuscript, its spacing, even perhaps the intensity of the strokes, its strange calligraphy? Or perhaps it’s simply worth searching out the original documents for oneself…

Now let’s turn our attention to the harmony. The first chord, on the 3rd beat, is C major, the tonic. The next chord, on the downbeat, is also C major. And the third chord is a Dominant chord. If we look only at the relative dissonance between the three chords, the Dominant ought to receive the most weight, yet it doesn’t.

So now we need to look at the Meter. The downbeat always has an innate accent potential. And indeed the energy does center on the downbeat. Metrically, it makes sense that the Pillar should be on the downbeat.

Now let’s look at the relative note-values of the principal line. It begins on C with a short note, then moves to G on an even shorter note, and finally settles into a second G on a very long note. This G on the first downbeat is where the energy centers, and therefore its placement works logically on that level.

Now consider the Note-height relationships of the top melody: C-G-G. It begins on a Treble C, then descends a perfect fourth to G, and then the G repeats. Vocally, the C, being the highest pitch, should be the energy center, and indeed, many singers would try to sing it this way, but would be mistaken. Many early, Romantically-inspired editions of Beethoven interpret it this way as well. Even Schenker, in his edition of the complete Beethoven Sonatas, treats this initial gesture as if a Victorian sigh, adding in a diminuendo:

{Notice also Schenker’s insertion of a crescendo-diminuendo in mm. 3-4 (not ill-conceived if interpreted on a small scale) and also notice how the crescendo in m. 5 peaks on the third beat rather than the following downbeat, as in Beethoven's hand, deftly destroying the composer's much simpler and more powerful indication. In Schenker’s view, the treble G (both of them, it seems) represents the melodic pinnacle of the phrase, both because it’s the highest note and because it falls on the fifth (Dominant) degree of the scale, which has inherent melodic tension (a Schenkerian theme). The first G however is merely the preparation of the following G on the downbeat, and only one of the two can rightly reign as the first major Energy Pillar.}

Returning to our previous argument about the phrasing of the initial gesture, it would be enough to conclude that since the Meter AND the relative Note-value favor the long note on the downbeat of m. 1, despite its relative consonance to the Dominant and its melodically lower placement, we can feel confident in choosing the downbeat as the first Energy Pillar. After all, most feel and play it that way instinctively; ultimately, both personal and mass intuition must be relied upon to make the final decision.

Again, some vocally-inspired pianists give an expressive accent to the initial C in the melody because it’s higher. There’s a fleeting beauty in this, but this is Beethoven, and beginning the last movement of his last of 32 Sonatas as if he were introducing Chopin seems like an affront to his legacy.

Other harmonically sensitive pianists, feeling the relative dissonance of the Dominant on the 2nd beat, insert a small, expressive crescendo, as if apologizing for its misplacement. More Chopin to my ears.

What’s missing here in traditional notation is the realization that the two C-major chords are not the same chord! How often I coach singers to realize that just because two identical notes are side-by-side doesn’t mean that they share the same color or meaning! Listen to the harmony surrounding them, to the rhythm, to the movement of the line. Everything affects the color of two seemingly identical notes, making them quite different. An E, for example, might be the major third over a C major chord one moment, magically transform into a major seventh above an F major chord the next, and then become the sharped 4th resolving up a half-step above a B-flat major chord. The meaning and resulting color constantly change according to surrounding harmonic and melodic movement.

Chords work the same way. They can often be interpreted simultaneously on several different levels. Try to reach their functional level – the level that means most to the performer. If the second C major chord in the example feels dissonant against the following Dominant chord, where does this dissonance come from? How can you explain it? The reason it feels dissonant is that rather than being a tonic C major chord, it’s a Sub-dominant C major chord, acting as a chordal appoggiatura to the following chord.

I notate it like so:

An appoggiatura is a leaning note, a point of tension that dissipates as it resolves into the following note. Likewise, a chordal appoggiatura is a chord of inherent relative tension that resolves into the following chord. In both cases, the tension and its resolution form one single entity, taking on the combined rhythmic value of the two, such that a quarter-note appoggiatura resolving into a quarter-note resolution is best felt as a single half-note that changes pitch and intensity level. If you conceive of an appoggiatura and its resolution as two separate events, you’ll never express its true nature.

The following gesture works exactly the same way, and can be notated traditionally like so:

Or more explicitly, like so:

Seen in this light, it all makes sense. The relative harmonic dissonance that the interpreter feels is not ignored – it’s observed for what it truly is! You’ll no longer have to resist your romantic desire to express relative harmonic dissonance, because by interpreting the second C major chord as dissonant rather than consonant, you can naturally phrase it romantically while remaining quite classical and pure. This is theory and analysis in action for the serious performer.

Let’s now take a step back and try to define the larger movement and subdivisions of this seamless, cryptic initial 8-bar phrase. A typical, classical 8-bar phrase divides into 3 units: 2+2+4, with the climax in the third unit. This example divides though more precisely as 1+1+2+4; therefore, there are four pillars, each of subtly growing intensity.

We’ve already defined the first two gestures and their respective Pillars, so now let’s look at the third:

Where is its energy-center?

How do you define its harmony?

It’s sometimes best to define the harmonic movement of a given passage by the key of the arrival point, in this case a chordal appoggiatura IV-I over G major, the Dominant. As you approach the Dominant, Tonic chords morph into Sub-Dominant chords of the Dominant. That is, the C major Tonic chord reinterprets itself as the Sub-dominant of G major even before the ear fully realizes it. In this passage, as it’s unaccented, it serves as a magical bridge to a new realm, fleeting as it were.

What happens in the following measure is even more fantastic – the C major chord unwittingly becomes the VII chord of D minor, again acting as a bridge between parallel realms. This chord, accented with a poignant, softly piercing melodic 4-3 appoggiatura finds its heightened tension from being effectively the (minor) Dominant of the Dominant, and in the next two bars, the tension retreats through the Dominant and then resolves, almost stoically, into the Tonic, now completely transformed. The colors of C major! It’s a truly wondrous passage, and it pains the ear to so often hear it performed as if every C major transformation were merely the Tonic.

After you’ve defined the Pillars and organized them, the next step is to ask yourself what each of them makes you feel. Choose several adjectives that immediately come to mind. After you sketch out what it is you feel, try to decipher why it is that each Pillar inspires the given emotional responses. Then as you prepare to realize your intentions at the Piano, allow yourself to exaggerate your responses so that you can fully claim them and control them. Be luxuriously sensitive, lavishly expressive. At this point, you can then release control and follow the emotional pathway you’ve set for yourself. Like a good actor, you’ve prepared the affect that you find most true and then realize it with the freshness of spirit that the audience will possess when they hear you perform it.

We’ve only touched the surface in this Introduction to Performance-centered Analysis, but I hoped to have shown that Theory needn’t be dry and detached; indeed, analysis is the soul of mature interpretation. It’s what gives meaning and form to emotion and movement. All analysis in the end is simply explaining and understanding of the ebb and flow of emotional tension. As you take apart the scores you prepare, your analytical skills will improve, and I dare say that your understanding of your very self will become more true and complete. Is not this the goal of all artistic endeavor?