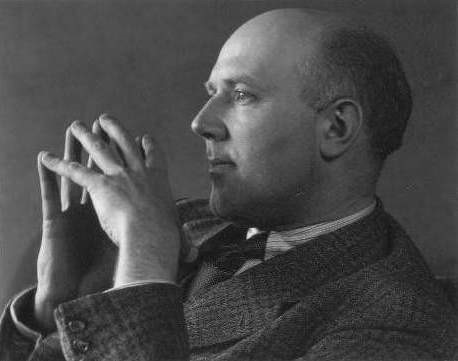

I devoured all of his recordings and took up Rachmaninoff’s Third Concerto, imitating every nuance of Horowitz’ legendary interpretations of it. After a few months, I reached my first Horowitz saturation point – I simply couldn’t take any more. Everything I loved about it started getting on my nerves. Then I would come back, over and over again, the cycle always repeating itself.

I simply couldn’t figure out Horowitz, and that bothered me and captivated me. All artists can be defined and categorized, but Horowitz is an Enigma: as soon as you have him briefly pinned down, he morphs into another entity and contradicts you. His strengths are as many as his weaknesses. But he never ceases to fascinate. No other pianist has been written about and analyzed so extensively, so I’ll leave you to their commentaries, but there are two extremely important aspects about Horowitz’ language that are usually glossed over or misunderstood: his willfulness and his acceptance of Brass and Percussion as an integral part of orchestration.

The most common argument about Horowitz’ approach is – He would be great if only he didn’t do such-and-such, if only he didn’t do such-and-such. I used to approach him like that, trying to imitate only Horowitz’ proper qualities, excising what shouldn’t be there. But what I was left with was often meaningless babble.

And this is so often true – take away what you don’t like about something, and you may be removing the very reason why you like it so much.

Horowitz will sometimes willfully mangle part of a phrase, making you sit on edge and gnaw your teeth, close your ears and cringe. You want to scream out, Why do you have to do that! And then the next moment, he’ll play the most beautiful, dissolving, nostalgic phrase, and you’ll swear that you’ve never heard such a beautiful passage. You’ll love him again and know him for the poet and seducer he is.

Yet take away the first part, and what’s left? Dribbling nonsense. Horowitz never gives you anything important without somehow making you want it first. This is part of his genius. He knows how to balance love and hate, creating the most romantic, extreme contrasts. And it becomes addictive. You want him to bend the phrases against your own design so that he can then apologize and set everything right again.

Horowitz’ least successful, least personal playing, are his recordings with Toscanini. Yes, they’re fantastic recordings nonetheless, but these two giants of interpretation were simply not meant to make music together. It’s as if they’re speaking to each other in Chinese, one in Mandarin, the other in Cantonese.

Horowitz is the weaker Artist in the meeting. He was intimidated by his Father-in-law and wanted to please him and be accepted by him. He plays the Emperor and Tchaikovsky’s First in a quite normal, proper way. You still hear Horowitz underneath but he’s in a straitjacket, smothered. Listening, you long for him to break free, but he doesn’t. It’s disingenuous playing, masterful but false.

Later in his life, Horowitz could often become a caricature of himself, taking things a step too far. But even this was at least Horowitz. His sin was loving opium. Take his late recording of the Liszt Sonata. It’s like a series of character pieces, broken up and torn down at every opportunity. But what colors! What poetic hallucinations! Contrary to common opinion, this is for me far superior to his earlier recording, which is full of momentum and verve and holds together architecturally much better, but lacks the tonal imagination and attention to detail. When he plays Liszt, the devil and angel in him meet in the most perfect balance. He is Liszt incarnate.

He has a similar chemistry with several composers, Rachmaninoff for example. The composer admitted that Horowitz played many of his works – the Third Concerto, for instance – better than himself.

And Scriabin! And Scarlatti! The list goes on and on. But let’s move on to the second important feature of Horowitz style, indirectly related to the first and usually overlooked or misunderstood – his percussiveness.

Horowitz imitators are the noisiest pianists around. It’s not nearly as common as it was thirty or forty years ago when every Conservatory pianist was trying to play as fast and loud as Horowitz. Students pick up on his power without understanding its source or being able to define its substance and think they can capture it by simply flailing away at the keyboard.

I myself admit to having occasionally fallen victim to this trap. Inspired by a Horowitz recording, I go to the piano and try to recapture its magic; after a couple days I think I’ve managed somehow. Then I listen again. It’s not nearly as percussive or loud or heavy as it seemed in my memory. It simply rings with a golden shimmer. The weight doesn’t stay in the sound; it passes through it like electricity. The effects often seem much greater than they actually are because of the way he places them in time and constrasts them against opposite colors, or against silence. In his phrasing and in his voicings, he pinpoints the exact notes to point up for maximum effect. He searches out the dissonant intervals, melodically and harmonically, and heightens them. He doesn’t smear colors or effects over groups of notes – he crafts each note individually.

Unlike most pianists, Horowitz isn’t afraid of Percussion and Brass – he embraces them as friends. He uses them sparingly but always at just the right moment for maximum effect. Only in Horowitz do you think he’s reached a triple forte only to be suddenly hit with a chord twice as loud and powerful! Yet he rarely actually offends the ear as many of his imitators do. He punches you in the gut and sends you reeling. And you stand up smiling and come back for more!

Gilels is another pianist that embraces Percussion and Brass, but he does so in a much more muscular, bulky way. Horowitz slaps much more often than he punches; he plays with you and provokes you, but he saves real punches for maximum effect. Magic is not a heavy entity – it floats and can never quite be pinned down, and Horowitz is the ultimate Magician.

Horowitz’ Percussion is very rarely percussive; he embraces Percussion as a light, singing force. He uses it as a great orchestrator does - to highlight phrases, to create contrast, to clarify structure. And among the Greats, he is absolutely unique in his acceptance of Percussion. None of the Golden Age pianists understood Percussion like Horowitz – they all shied away from it, searching for the ever-elusive golden tone. Oddly, that ideal generally possessed little gold or polish; it has more of a matte finish. Listen to the entire Leschetizky School, for example – all possess an almost identical sound, singing, round and translucent. Horowitz’ sound, at least in the melody, is rarely as beautiful or pure – he leaves a certain edge in it that gently attracts the ear to it. Horowitz does possess the Leschetizky sound, but he usually hides it from view.

Why conceal beauty? This is a mystifying feature of his language – Horowitz often veils his most beautiful sounds underneath the surface, lending the overall effect a complexity and beauty that often surpasses the greatest of the Golden Age pianists.

The conundrum for a pianist wishing to experiment with percussive effects is – where do you use them? If you put them in the melody, the tone-color of the melody becomes less beautiful. If you put them underneath the melody, they distract the listener’s ear from the melody and generally destroy the effect.

Horowitz deliberately uses brighter, less beautiful colors in the melody, against common logic. And this is revolutionary! The proof of its effectiveness lies in his recordings. An added bonus of this approach is that the melody naturally has more carrying power in a large hall. Brighter sounds ring more and often carry better.

Remember also, brightness in a small space never sounds as bright in a larger space. The larger the space, the duller the effect, and the greater the need to increase the scope of everything.

Finally, Horowitz’ embracing of Percussion and Brass is one of the features that sets him off as Modern against the previous generation of pianists.

In Horowitz, fire sings through metal, glass, water and ice.

The monotony and solitude of a quiet life stimulates the creative mind.

Albert Einstein