Have you ever wondered how a maestro comes to be? How does one achieve such a state of divine pretentiousness?

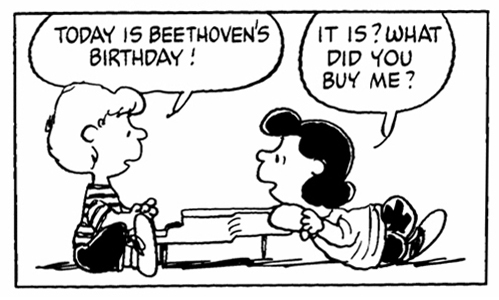

I can't speak to how any of my colleagues managed it because it would be beneath a conductor of my stature to fraternize with a competing baton-wielder, but I suppose my path is not unusual. I started out as Schroeder.

In fact, one of the very first tunes I learned was Peanuts, and you might say it was my unofficial theme song. The other day I was cleaning out my closet (actually just reshuffling chaos) and came across a feature story about the maestrino at 18. It's fantastic – I was already spouting the sort of nonsense that would guarantee both my ascent and descent to the podium, although I didn't know it yet. The likes of: "If you have focused energy, like electricity that just keeps moving and never stays static, then that's what the audience really picks up on... It's movement, more than anything, it's movement." What the heck does that mean?! ...Exactly. That's part of the craft, and it's probably inborn: never tell the audience – or God forbid the orchestra – anything that really makes sense or they'll quickly sort out that you're a fraud. (But that's just between us girls.)

So here it is, David at 18:

Focus...

energy...

practice

KEYS

to a life in music

By Michael Hallinan, The Herald, Everett, Washington. Sunday, Dec. 5, 1993

Ten o'clock on an October morning, 1987. Robin McCabe, concert pianist, faculty faculty member of the University of Washington School of Music, formerly of Juilliard, answers a knock on her studio door. She looks down to find a 12-year-old, sandy-haired boy in full tuxedo. He is David Wolff, and he has achieved something of a name for himself in his hometown of Lake Stevens. His piano teacher of five years, Patricia Reeve of Snohomish, knows the time has come for her talented pupil to move on to another instructor. She has prevailed on McCabe to give the boy an audition, and she has prevailed on her student to wear his tux.

"She was very much into stage presence," David remembers now. "I remember walking down the hall and everybody was looking at me. I must have looked like a little clown."

"So he came in a little tuxedo at 10 o'clock in the morning and played some Bach," says McCabe, who this year was named the School of Music's associate director for performance and public affairs. "l could see right away there was definitely something worth working for. It doesn't take too long to smell talent."

Fast forward six years, to Nov. 6, 1993. David Wolff, 18, stands calmly in the wings of the Everett Community Theater, black suit, white shirt, maroon tie, looking like the boy next door waiting for his date. The houselights dim. The audience of about 250 muffles its chatter. David steps into the light and glides with a loose-limbed athletic grace to a Steinway concert grand at center stage, turns and acknowledges applause with a bashful bow.

He sits at the piano and launches into the biggest performance of his young life.

Six years ago when he auditioned for McCabe, David began serious studies toward his hoped-for career as one of the handful of musicians who make their livings as international concert pianists. With this piano recital he marks the beginning of the end of that period. Now it is coming time for him to move on to one of the nation's elite music conservatories, Juilliard, for instance.

David is the third of four brothers, each exploring his own musical niche. Tom, 23, is into the Seattle grunge rock scene. Josh, 20, who shares student digs with David in Seattle's University District, is a jazz pianist. Dan, 17, a Lake Stevens High School junior, composes and performs with a friend as a Christian music duo, Statement of Faith.

Their father, Ron Wolff, is a commercial contractor specializing in building store interiors in shopping malls. Their mother, Christie Wolff, tutors private students in English. Mrs. Wolff began piano lessons with Reeve when the boys were young. Her practice time became the hour of household quiet after the boys' bedtime. "So we'd always go to bed hearing music," David recalls. "I'm sure that's what sparked my interest"

At the age of 6, David declared that he wanted to learn the piano. But Reeve wouldn't take him for another year, until he developed more both physically and emotionally. Within about three months of starting lessons, Reeve was aware that David was a student of special talent and dedication. It was becoming clear that he was special in other ways too. He was placed in the gifted students program at Lake Stevens Elementary, and he skipped fifth grade. He also showed prowess in athletics, particularly in soccer. He applied the same dogged determination to practicing soccer as he did to practicing the piano. Now he skis occasionally and plays volleyball and tennis, but he avoids activities that risk his hands. ''It's just not worth it to me to take the chance," he says. "If I were to break a finger, that would take a lot away from practicing, and it might even take away from what I can get out of the piano."

At 18, David has grown into a gentle, thoughtful young man with a keen mind, a kind heart, an earnest soul and an iron-fisted will. This willpower allows him to focus his attention with withering concentration for prodigious periods of time. Such willfulness is called dedication in a young man bound for Carnegie Hall. In an ordinary kid, it's called ornery.

David Wolff at 12 performing at the Lake Stevens Aquafest, in a family snapshot

Take the typical stay-at-the-table-until-you-eat-those-vegetables routine. "Those were kind of long evenings at the table," David says. "I was pretty determined not to eat them." His will prevailed. For years, he ate only spaghetti and pizza.

David became unhappy with school in seventh grade. He wanted to be home practicing the piano, and he knew he could learn more in less time on his own. Again he dug in. "He stubbornly just turned off something inside and wasn't going to let them reach him," his mother says. "So it came to be a kind of a standoff, and we decided we couldn't let that go on any longer."

So David took charge of his own schooling, supervised, lightly as it turned out, by his mother. He basically skipped high school and attended Everett Community College instead at 15. There he became fluent in Spanish in one quarter and learned enough French over spring break to begin instruction with the third-quarter class. Now he is learning Korean because one-third of Juilliard students are Korean.

At 18, David is the age of most high school seniors; instead he's a senior at the UW, where he was admitted in 1991.

David's recital program, prepared in partial fulfillment of his degree requirements, is the largest he's yet attempted, about 80 minutes of music involving hundreds of thousands of notes, all committed to memory.

"Memorizing has always been something really natural for me," David says. "If you have something in your ear, then you don't need to be looking at every note on the page because you know what it sounds like."

After the notes are memorized comes the physical labor of discovering, through precise muscle movements, how to translate those notes into music. A month before David's Everett recital, the notes are long since memorized and the physical work is fading to the background. Now he is paying more attention to the music, to the articulation of phrases, to the connections and relationships within the compositions.

"My first goal is that I can communicate an idea," he says, "a composer's idea and my idea about that, to an audience . . .. So it's not just a show, so it's more of a communion, a sharing of the music."

David loves to perform. Performing is an elevated state of emotion, he says, a sense of soaring. When be was 12, he played the first movement of Camille Saint-Saëns' Piano Concerto No. 2 with the Everett Symphony Orchestra, his orchestral début.

"That was really exciting for me. I remember feeling on top of the world that performance," he says.

That was a crucial year for David, who by then was controlling his own education and beginning piano studies with a top-flight teacher. David recalls his audition with McCabe: "She said to me, 'If I agree to take you as a student, you will do everything how I want you to do it.'"

With David's iron will, that was a significant concession. But McCabe has a will to match David's, and she has something more: authority, and a piano teacher's well-tuned instinct for when to wield it. Early in their studies together, McCabe assigned Bela Bartok's Piano Suite. David prepared it for the next lesson, and McCabe assigned him to work on it some more.

"I was kind of tired of it, so I didn't practice at all that week," David remembers. Seeing no progress, McCabe instructed him to bring it back the following week. But on the third week it was even worse, and on the fourth week McCabe gave up.

David Weatherford (right) congratulates Wolff after a recital. Weatherford, a top Seattle Interior Designer, has been Wolff's patron

But she had only conceded the initial skirmish. The showdown would come later, in Victoria, British Columbia. In the spring of that first year together, McCabe took her new student to perform at a music festival on Orcas Island. During a poolside reception, 13- year-old David chatted with David Weatherford, a top Seattle interior designer, who explained he raised money for talented artists as a member of the King County Arts Commission.

The budding pianist had been wanting to go with McCabe to the Johanessen International School of the Arts in Victoria. McCabe and some of her former Juilliard colleagues and their promising students summer there. But the Wolff family, with four growing boys, couldn't afford it.

Soon the two Davids were discussing money, $2,500. "I said, I can't give you $2,500," Weatherford recalls, "but I can give you $250 and find nine other people who'll do the same.'' David Wolff had found his patron. Each spring since then Weatherford has arranged a private recital to raise funds for another summer at the Johanessen school.

That first summer In Victoria, David was 13, away from home and testing his limits with his piano teacher, unaware that the showdown was looming.

Within the first two weeks, McCabe told David to play for two other teachers at the school, and she specified the pieces. "But I had in mind what I wanted to play," David remembers, "and so I thought, well, I could play this piece or play this piece, no big deal." McCabe also instructed David to attend a faculty piano recital. He didn't.

"And then I went to my lesson and got my music out, and she said, 'You won't need your music today." McCabe asked what he had played for the other music instructors, and he admitted he had not played what she'd asked. She asked about the recital. I said, 'You know, I was going to go to the concert like you said, but then I thought I really needed to practice for my lesson today, so I ended up not going.'

"That's when ... I knew it wasn't going to be a good day for me," David says.

McCabe ordered David home for the summer. He staggered out. "I remember going in the field and thinking, 'Oh, I should never have started studying with this person.' " He thought of Weatherford and the donors who footed the bill for the summer.

"Oh no, I can't go home. Oh, that would be terrible."

The next day, contrite, he promised to follow McCabe's instructions. She agreed to give him one more chance. "If you mess up once, I'll drive you to the ferry docks," he remembers her warning.

Musicians often speak about the musical line, referring to the sense of connectedness from note to note that is usually, but not always, carried by the melody. To David, line is all-important. "In instrumental music, basically we're trying to imitate the human voice. As a pianist, every time you play a note the sound just starts decaying, and so you have to connect it to the next note so it sounds even. To imitate the human voice is really an illusion because every note is decaying, but you're sounding like it's not.

"The line, that is the thought. That's the direct thought, the communication. It's like a sentence. It you stop (a line) in the middle, that's like saying, 'I am thinking that..."

The structural beauty of Johann Sebastian Bach's exposed lines captivates David's imagination, and over the weeks of preparation for his recital he practices his opening piece, Bach's Partita No. 2 in C minor, with a fierce fascination.

David likes to find a practice room about 6 p.m. as the Music Building quiets from the daytime hubbub of tuning instruments and practice scales. Not infrequently, he'll stay until 1 or 2 a.m.

"Something I was thinking about last night," he says one morning after a long and fruitful practice, particularly with Bach: "A lot of people say you have to make a long line. But I was thinking that the process of practicing is eliminating anything that would block the line."

He traces his finger in the air, envisioning electrical arcs. "If you have focused energy, like electricity that just keeps moving and never stays static, then that's what the audience really picks up on... It's movement, more than anything, it's movement."

As recital day approaches, the concert centerpiece, Sergei Prokofiev's Piano Sonata No.6 in A minor, is in good shape. It is a work David has studied deeply.

Sometimes called the "War'' sonata, it is a large, unwieldy work, full of dissonant clashes, chaotic layering of sound and a pervasive sense of anguish.

Wolff (right) discusses his playing with Matt Goodrich and other students in a performance class at the University of Washington

"The first time I played Prokofiev, the first movement, in class was last spring, and my teacher said, 'David, there's already enough noise in this world, maybe you could try to make some music out of it?" He put several hundred hours of practice into the Prokofiev over the next nine months.

"I feel like it is really becoming more a part of me," he says 11 days before the recital."It's really coming together as a whole more and more. The first movement, which used to seem the biggest thing in the world, it seems now like one picture."

Still, the Bach is taking up huge chunks of practice time, and with McCabe's permission, David substitutes Frédéric Chopin's Scherzo No. 3 in C sharp minor, a work with which he is already familiar, for the Scherzo No. 4 with which he originally planned to close the program.

Three Claude Debussy preludes planned after intermission also need work, and time is running short. With just a few days to go, David substitutes Debussy's "Estampes," another work he already knows.

Two days before the recital he runs through the revised second half of the program. He feels comfortable with it. He plans to run through the more challenging first half of his program on recital day, but the day does not go as planned. His arrangement for recording the concert goes awry, and he and his parents spend scarce hours improvising a new plan.

So as the recital begins and David launches into the Bach partita, he soon realizes that his fingers aren't quite doing as he wills. David likes to take Bach's final movement at breakneck speed. Listening to him hurtle through it on the ledge of control excites a lurid thrill, like watching a motorcycle daredevil fly over a phalanx of buses.

But on recital night David's balky fingers make him cautious, and that fatal attraction is lost. He plays the Bach well; he knows he can play it better. Nevertheless, he now thinks not of Bach but of Prokofiev. The biggest piece of his program is about to begin.

Despite the missed rehearsal, David's performance of Prokofiev's first movement is powerful and chaotic, yet musical nonetheless.

In classical music concerts, applause ordinarily comes at the end of a piece. Applause between movements is a spontaneous outburst of approval. David's audience applauds the Prokofiev first movement

The second half of the recital, now salted with works he knows well, is more relaxed, though it lacks the edgy challenge of the first half. Afterward, in the lobby, he chats comfortably with the people who are part of this landmark evening in his life.

Some who heard him might call a young musician of such exceptional talent a prodigy. But David dislikes the term.

"Whether somebody's a prodigy or not really doesn't matter," he says. " Basically, you have to get to a certain point. It doesn't matter whether you get there when you're 16 or when you're 25. "I think I'm getting there faster than some people and maybe slower than some other people. But I feel like I'm going to get there."