Linking and Separating

There is a Zen story about a man riding a horse that is galloping very quickly.

Another man, standing alongside the road, yells at him,

"Where are you going?" and the man on the horse yells back,

"I don't know. Ask the horse."

~ unknown

One of the most difficult challenges of Zen energy is getting out of your own way and letting the energy flow freely. What typically happens, even among good performers, is a constant pushing-forward of the energy so it doesn’t fall flat. It remains constantly present, slightly leaning into the future, even in ritardandos and dimuendos. There’s a great piece of advice for conductors that applies just as well to all musicians – It’s like holding a bird in your hand. Hold it too tightly and you’ll crush it; hold it too loosely and it’ll fly away.

A great deal of music-making is crushed – it’s given to the listener already half-dead. The danger in approaching music from a Zen perspective is the opposite – you relax so much that it flies away free but meaningless. As always, balance is the key.

When I feel the line breaking, I often experience what I can only describe as a vertical line in my head blocking it. Once I identify the blocking energy, I’m able to remove it and the music flows again.

My first goal in purifying the energy is to unify each individual gesture, starting from phrase segments, then working up to whole phrases, then phrase groupings. Once I’ve cleared away the excess energy blocking the lines, I go back and deliberately enter punctuation marks to separate gestures and clarify their meaning. It was only around the middle of the 19th century that some composers (Liszt and Chopin, for example) started inserting commas and other punctuation marks beyond the traditional musical notation.

How does one gesture connect to the next? There are as many possibilities as there are in written language, and more, but here are the five most common punctuations between gestures and phrases:

1) and

but

or

because

2) , and

, but

, or

3) . . . .

4) ? …

5) ! . . .

In the first group of examples, there’s no comma, simply a conjunction. In the second, there’s a comma followed by a conjunction. In the third, a full stop (period). In the fourth, a question mark. The fifth, an exclamation mark. This subject alone is material for a full book that’s surely already been written and I won’t belabor it, but it’s important to realize that it’s usually the interpreter’s responsibility to insert punctuation marks into his score as specifically as possible because the composer generally leaves it up to us.

And how often a simple punctuation mark, the slightest pause or lingering, clarifies the architecture and meaning of an entire section, sometimes even making or breaking an entire work!

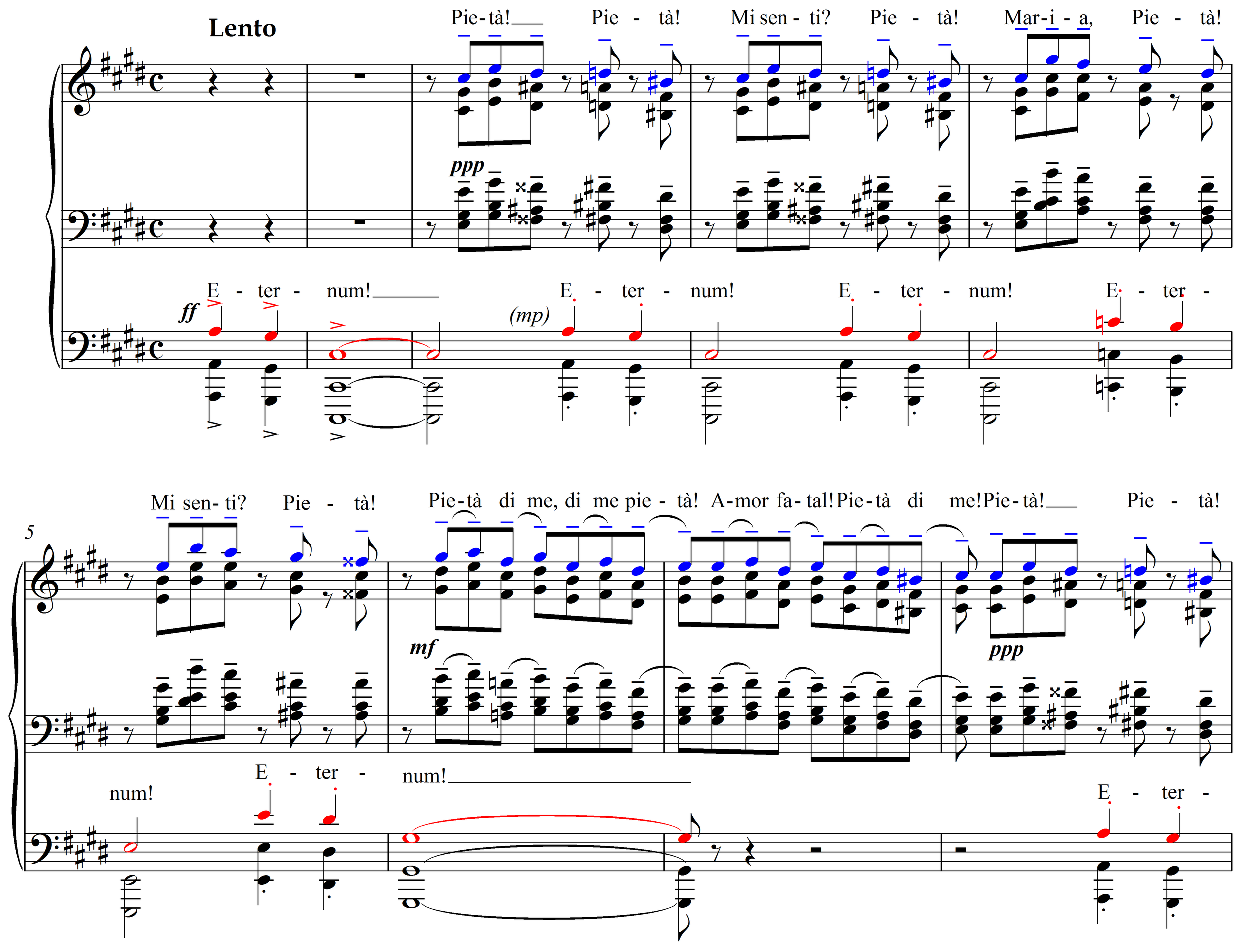

Let’s look now at a few examples from our Prelude. Imagine it for a moment from a Verdian perspective. The heroin has been condemned to death for killing her own brother as she rescued him from certain death. There’s a great chorus of monks chanting in Latin from inside the Cathedral, “Eternum! Eternum! Eternum!”

From her cell she laments, in Italian, her wretched state:

“Pietà, pietà! Mi senti,? Pietà! Maria, pietà! Mi senti? Pietà!

Pietà di me, di me pietà! Amor fatal, pietà di me!”

Sing and play your way through it a couple of times. Do the words and their punctuation affect the way you play the passage?

Try creating your own operatic scenario and lyrics.